1675-1677

New England, North America

The discovery of the New World (North and South America) by Columbus in 1492 launched a race by Western Powers to stake claim to the land and riches thought to be available in this New World.

The Kingdoms of Portugal and Spain quickly established themselves as masters of the New World, particularly South America and southern North America. By defeating various Native American empires, states and tribes, notably the Incas and Aztecs; Spain established one of the largest empires in history. Amazing riches were obtained from New Spain, especially abundant gold and silver. Spain quickly became the richest kingdom on earth.

Eager to gain similar riches and territory, other European states sent their ships to the New World as well. The English, French, Dutch and even the Danes and Swedes staked claim to lands in the New World not yet controlled by Spain or Portugal, mainly small Caribbean islands and lands further north in North America.

The English first landed in North America in 1497 when John Cabot, an Italian navigator, was given permission by King Henry VII to find a northern route to the Far East. This early landing gave the English crown legitimate claims to the lands in present Canada and the eastern coast of the United States.

English settlers rapidly settled along the eastern coast of North America, gradually moving further west into the interior of present day Canada and the United States. Native American Indians at first welcomed or reluctantly accepted the new white settlers. Many Indians in fact coexisted in peace with the English, trading with the colonists and even living among the settlers.

However, as the English population expanded in the new English American colonies and more land was possessed by the settlers, hostility and rage grew among many Indians against the English. Sporadic skirmishes and battles between the Indians and the English increased in frequency. Over time, both the Indians and the English found themselves in a constant state of battle.

Finally, tensions became overwhelming and full scale war broke out in 1675 in the northern part of New England, now known as the states of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and surrounding areas.

King Philip’s War

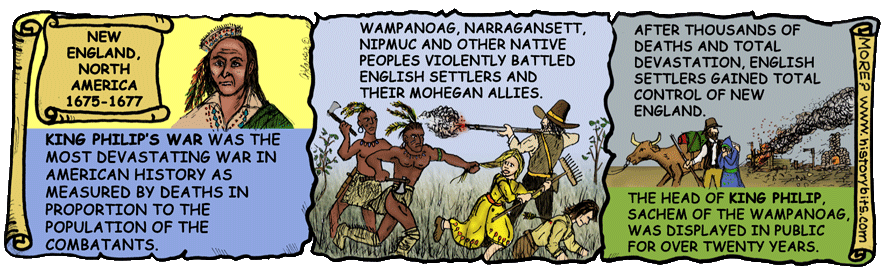

What became known to history as King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was the most devastating war in American history as measured by the percentage of casualties in proportion to the population and total destruction of the towns, villages and lands throughout northern New England. Over ten percent of the soldiers on both sides of the conflict were killed or wounded. The extent and savagery of the war threatened to push the English settlers out of America entirely.

King Philip’s War was named for King Philip (Metacom or Metacomet was his Native American Indian name), the son of Massasoit (Ousamequin) and chief of the Wampanoag tribe. Philip became sachem or chief upon the death of his brother Wamsutta. King Philip and his tribe lived for years in peace with the English colonists. However, tensions and events soon overwhelmed the Wampanoag and the peace was to be broken.

Wamsutta, the then sachem of the Wampanoag, was ordered to appear at an English court to answer unknown charges. Wamsutta was captured by English militia and put in captivity. Wamsutta became ill and died of his sickness in captivity. Many Wampanoag believed that Wamsutta was murdered at the hands of the English. The Wampanoag were incensed at the death of their Sachem and demanded revenge.

King Philip became the new Sachem and tried to ease the growing tension and anger within his people. Despite efforts of Philip to maintain peace with the English, the lingering resentment of Wamsutta’s death, the growing dependence on English foodstuffs, tools and other supplies and the steady stream of forced land sales of Indian land to the English, angered and infuriated the Wampanoag and other Indian tribes.

Destruction of Swansea

In the spring of 1675, a local Indian who had converted to Christianity and may have been an informer for the English was killed. Philip may have ordered his death. English authorities seized and tried three Wampanoags for the murder and were executed. Vowing revenge for these deaths, the Wampanoags in June, 1675, raided the English border town of Swansea and destroyed it, killing many whites. Nipmuc, Narragansett and other Native American Indians joined the Wampanoags and further attacks commenced across the region; English towns were destroyed and white men, women and even children were massacred. Havoc played across the entire region. The War began in earnest.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony, upon hearing the news of the Swansea attack, rushed militias to help Plymouth Colony deal with the Indian threat. A hastily formed English army reached Mount Hope searching for the Wampanoags. The Indians were gone but left a warning for the English – severed, bloody English heads mounted on wooden poles.

More and more farms, towns and even forts were attacked and destroyed across the entire region. Devastation was everywhere. Numerous dead bodies of English, Indian and farm animals were strewn about the colonies. English colonial militias hurried to gather men at arms and sent them out to engage and destroy the Indian attackers.

Indian Advantage

Early in the War, the Indians had the advantage in battle against English militias and armies. The English, some being veterans of the great Thirty Years War in Europe, still retained the European style of warfare. Soldiers marched very closely together and as they neared their enemy, they collectively shot a volley of musket balls towards the enemy ranks. This European style of warfare was ill suited to the terrain of New England with its thick woods and hilly landscape. Indians hid behind trees, bushes and boulders and shot either muskets or bows and arrows at specific, individual targets. The English were quickly dispatched by often unseen Indians hiding in the woods.

Quickly, the colonists began adopting the Indian style of warfare. Multiple Indian battle victories leading up to the Great Swamp Fight convinced the English to fight the “skulking way” of war, the superior Indian warfare style. Further, the English were fortunate to have Mohegan, Massachusetts, Pequot and Nauset Indian tribes join them in their battle against the Wampanoag, Narragansett, Pocumtuck and Nipmuc tribes. Having skilled Indian warriors helping the English greatly enhanced their ability to fight in the new “American” style.

Benjamin Church

Benjamin Church (1639-1718) was one of the most famous persons of the War and is now considered the Father of American Army Rangers; elite, specialized military forces. Church was one of America’s greatest Indian fighters and is credited with helping the English forces to learn from their Indian foes and emulate their battle style. He mixed traditional Puritan/European organizational and disciplinary tactics with Indian stealth, camouflage and ambush tactics. More than once, Church and leaders who learned from Church silently marched into Indian Territory and ambushed and killed Indians caught completely by surprise.

The End of the War

By midyear 1676, the war had started to wind down. Narragansett Indians, with their Sachem Canonchet killed, were completely defeated. The town of Hadley was attacked but Connecticut militia turned back the Indians. The Colony of Massachusetts offered an amnesty for Indians if they surrendered. Many Wampanoags and Nipmucs, wounded, tired and hungry, accepted the amnesty.

By early summer, a Major John Talcott and his army marched through Rhode Island and Connecticut, defeating and capturing large numbers of still warring Indians. Many Indian prisoners were shipped to the Caribbean Islands and sold as slaves.

Captain Benjamin Church and his troops marched through Plymouth attacking and defeating Indians who had not yet given up. Almost two hundred Nipmuc Indians surrendered in Boston. Finally, Captain Church and his men captured King Philip’swife and son, further demoralizing Philip and his remaining warriors.

King Philip himself was betrayed and his sanctuary fortress in Mount Hope, present day Bristol, Rhode Island, was revealed. An allied Indian under Captain Church’s command killed King Philip in his hideout and the War effectively ended.

According to transcripts written by Increase Mather, “… King Philip was taken and destroyed, cut into four quarters, and is now hanged up as a monument of revenging Justice, his head being cut off and carried away to Plymouth, his Hands were brought to Boston”.

The head of King Philip, Sachem of the Wampanoag was displayed on a pole for over twenty years.

The Wampanoags and their allies were virtually eliminated; killed, sold into slavery, reduced into local servitude to the victorious English or dispersed far away from their original homes in the New England colonies.

The Aftermath

Over half of New England’s towns were attacked during the war. Over 1,200 homes were burned and destroyed and over 8,000 precious food cattle killed. Countless amounts of food, supplies and personal belongings were totally destroyed. Approximately 800 English died in the war and measured against the small total population of New England at the time, the death rate was nearly twice the death rate of America’s most costly war, the American Civil War. Moreover, this proportional death rate was seven times the death rate of Americans killed in World War II.

Although rarely remembered today, King Philip’s War was a sad and deadly event that forever changed the history of the United States by enabling the English to gain total control over their colonies and to permanently establishing a new country in the New World.