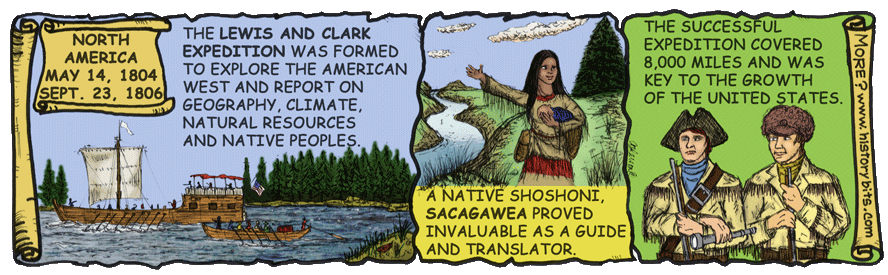

MAY 14, 1804 – SEPTEMBER 23, 1806

NORTH AMERICA

The Lewis and Clark Expedition is one of the most important events in American history. This historic adventure helped launch the young United States on a path that turned a small, coastal country into a continental power that would shape human history.

Reasons for the Expedition

On January 18, 1803, President Jefferson requested monies from Congress to pay for an expedition to explore the American continent, gather information and knowledge and report on climate, natural resources and native peoples.

Jefferson’s request stated: “The interests of commerce place the principal object within the constitutional powers and care of Congress and that it should incidentally advance the geographical knowledge of our own continent cannot but be an additional gratification”.

This funding request was done in secrecy because this expedition would enter territory not part of the United States. The expedition would have to get consent from the French government as France laid claim to the huge Midwestern and western portions of the American continent.

As if an act of Providence, one of America’s greatest adventures gained significant assistance by the Emperor of France, Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon, intent on world conquest, was engaging his mighty French military in war across the entire European continent and beyond. The ongoing war was extremely costly and Napoleon needed to dramatically supplement his treasury.

Napoleon’s emissaries reached out to the young United States to discuss the possibility of selling the French Louisiana Territory in America to the United States. President Thomas Jefferson and the United States Congress jumped at this unparalleled opportunity to not only acquire the strategically important city of New Orleans but the entire French territory of Louisiana.

The famous Louisiana Purchase was announced on July 4, 1803, twenty seven years after the birth of the United States. This momentous purchase expanded the size of the United States dramatically. The small coastal nation doubled in size and now stretched across the continent past the Mississippi River and beyond.

Upon the acceptance of funding for the expedition, President Jefferson immediately began preparations for this strategically important expedition. Once the Louisiana Purchase was announced, the expedition was ready to begin.

Preparations for the Expedition

An intrepid scholar and adventurer himself, President Jefferson selected a former neighbor from Charlottesville, Virginia, Meriwether Lewis; a 28 year old Army Captain as the leader of this expedition. Lewis grew up hunting, trapping and exploring the vast woodlands near his home. He became a self-trained expert in the study of plants and animals. His military experience included subduing the Whiskey Rebellion while serving with the Virginia Militia in 1794.

Captain Lewis picked a former Army comrade, the 32 year old William Clark. William Clark was the youngest brother of Revolutionary War hero General George Rogers Clark. Clark’s valuable experience included fighting in the Northwest Indian Wars under General “Mad Anthony” Wayne.

Lewis and Clark spent considerable time preparing for this monumental journey. They met with the President’s scientific friends in Philadelphia for advice and scientific and medical equipment. They called on their neighbors at home and friends in various Army outposts both in the Virginia area and closer to their proposed expedition launching point near St. Louis, Missouri.

Special river boats were constructed including a custom made 55 foot keelboat containing a small cabin and sail. Also readied were smaller boats called pirogues. Supplies were assembled and staged for the beginning of the great journey.

In the spring of 1804, the two Captains had assembled approximately 45 men to join them. These men were composed of friends, military personnel and local boatmen, woodsmen and men familiar with Indians and their customs and language. Included in this group was a black man named York who would become a trusted companion to the Captains. Finally, Captain Lewis purchased a large dog of the “newfoundland breed” to accompany him. His dog, Seaman, would become his close friend along the journey.

The Journey Begins

On May 14, 1804 the great journey began when the Lewis and Clark Corp of Discovery Expedition broke camp at their staging location near the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers in the St. Louis area. Throughout the long and hot summer of 1804, the Expedition laboriously traversed the Missouri upriver.

Natural hazards abounded along the Missouri River. Sunken and hidden trees, collapsing river banks, high wind squalls, heavy rain storms, intense heat and constant clouds of mosquitoes, flies and other troublesome insects plagued the men.

The Expedition also had personnel problems. Two men deserted, various men were severely disciplined by flogging, a man was discharged on mutiny charges and a Sgt. Charles Floyd died of appendicitis, the only death suffered during the Expedition. Also, early in the journey, the Expedition faced a war party of Teton Sioux who tried to steal their boats and supplies. The Sioux retreated when faced with superior weapons from the Expedition.

The Journey Progresses Northwest

The Expedition moved forward through modern day States such as Missouri, Iowa, Nebraska, the Dakotas, Montana and more. In the fall of 1804 the men come across earth lodge villages of Hidatsa/Minitari and Mandan Indians. With winter approaching, the men built a small fort across the river from the Native Indian villages.

On Christmas Eve, December 24, 1804, the men moved into their new fort for the winter which they named Fort Mandan.

Relations were friendly with the Hidatsa/Minitari Indians. Through them, they met a French Canadian fur trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau. Toussaint had a Shoshone Indian wife name Sacagawea who was captured by the Hidatsa tribe. Toussaint, with his knowledge of various Indian languages and customs and his knowledge of the territory was hired as an interpreter and guide by the Expedition.

The addition of Toussaint and Sacagawea was a godsend to the Expedition. Not only did they help guide the men and interpret the languages of the main Indian tribes but Sacagawea also proved a special value to the men. Many of the Indian tribes that the Expedition encountered did not attack the men as the Indians believed that no women would accompany a threatening group or war party. Having a woman along with the Expedition was seen by many tribes as a symbol of truce and peaceful intentions of the Expedition.

Sacagawea gave birth to a baby boy, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, on February 11, 1806 in Fort Mandan. Captain Clark favored the boy whom he nicknamed Pomp, because of his pompous and confident attitude and dancing.

Exciting Experiences and Bountiful Learning

The Expedition, moving northwest after spending the winter at Fort Mandan, experienced great progress and success in achieving the goals of the Expedition. The men observed and recorded numerous new plant and animal species and witnessed great herds of buffaloes, elk, antelope, deer, large whales and more. Mountains, rivers, lakes and more were explored and recorded.

The Expedition experienced beautiful sights: the breathtaking Rocky Mountains, waterfalls, endless prairies, beautiful flowers, gigantic trees never seen before and much more. They also experienced severe snow storms, hot weather and many other character building challenges.

The men also met, interacted and traded with Native American tribes such as the Shoshone, Nez Perce, Clatsop, Sioux, Blackfeet and many more. Thankfully, mistrust and skirmishes between the Expedition and the various Indian tribes were minimal.

The Return of the Expedition

Spring, 1806

After reaching the Pacific Coast along the Columbia River, the Expedition began preparations to start the long journey home. New canoes were acquired from local Native Americans. Food, natural medicines and other supplies were prepared for the journey. Part of the Expedition obtained horses and rode along the river as they scouted ahead and hunted for food.

The two parties separated but reunited on August 12th near the Missouri and Yellowstone river confluence. They arrived at a village of Mandan Indians on the 17th. A member of the party left the Expedition at his request, to join a fur trapping party bound westward. The Expedition, now joined by a Mandan chief and his family traveled down the Missouri River on the final leg of their momentous journey.

September, 1806

With the current of the Missouri behind them, they were able to cover over 70 miles per day. The party was happy to have such speed as they knew that winter and its potentially harsh climate was soon to arrive. They were anxious to arrive safely home before the weather turned.

As the Expedition came closer to their home destination they began meeting boats of American traders and trappers heading upriver. The excitement among the party grew as they now knew they were very close to their home destination of St. Louis.

September 23, 1806

The Lewis and Clark Corp of Discovery Expedition finally reached St. Louis and “received a harty welcom from its inhabitants”.

The Expedition had traversed 8,000 miles of territory over two years, four months and nine days; a historical feat of exploration and endurance. Moreover, the Expedition was an enormous success, accomplishing all of the target goals assigned by President Jefferson. New and valuable information was gained concerning Native Peoples, culture, plant and animals, natural resources, usable trails, weather conditions and much more of this new and exciting addition to the United States.

Lewis and Clark were treated as national heroes. Congress awarded the officers and men of the Expedition, including Toussaint Charbonneau, with double pay, land grants and assignments. Unfortunately, Sacagawea did not receive any payments or land for her services.

Meriwether Lewis was commissioned Governor of Upper Louisiana Territory. Unfortunately, controversy arose around Lewis’s management of government funds. During a trip to Washington DC to resolve this matter, Lewis died of gunshot wounds on October 11, 1809 at Grinder’s Stand, a public inn located in Tennessee. It is unknown if his fatal wounds were from a murder attempt or if they were self-inflicted. He is buried within the Natchez Trace National Parkway near present day Hohenwald, Tennessee.

Clark was commissioned a Brigadier General of Militia and Indian Agent for the Upper Louisiana Territory. Later Clark became Governor of the Missouri Territory and Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

General William Clark was reappointed to his assignments by every succeeding President and he was widely admired and praised for his professionalism, honesty and care he gave to those he served especially the many Native American Indians under his jurisdiction. He died of natural causes in St. Louis on September 1, 1838 and is buried at the Bellefontaine Cemetery St. Louis.